India’s electric vehicle (EV) market holds immense promise as a cornerstone of sustainable transportation, yet it finds itself grappling with a persistent challenge: an overwhelming dependence on foreign supply chains, particularly from China. Despite aggressive government policies aimed at fostering self-reliance, the industry struggles to source critical components domestically, raising serious concerns about long-term growth and stability. With EV adoption gaining traction and nearing a 5% share of car sales, the urgency to address these dependencies has never been greater. The stakes are high, not just for economic reasons but also for positioning India as a global leader in EV manufacturing.

This reliance on imported parts isn’t merely a logistical hurdle; it’s a strategic vulnerability. Only a small fraction of EV models sold in India qualify for government incentives due to insufficient local content, exposing systemic gaps in the ecosystem. As the market expands, understanding the root causes of this dependency and exploring pathways to self-sufficiency becomes critical for stakeholders across the board.

Challenges in India’s EV Ecosystem

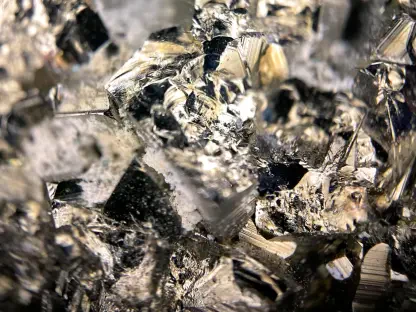

Dependence on Chinese Imports

The backbone of any electric vehicle lies in its core components, such as lithium-ion battery cells, rare earth magnets, and semiconductor chips, which collectively account for 50–60% of the vehicle’s total cost. Unfortunately, the majority of these high-value parts are imported, predominantly from China, leaving Indian automakers exposed to fluctuations in global prices and supply chain disruptions. This dependency stems from a lack of domestic manufacturing capacity for these sophisticated technologies, which require advanced expertise and infrastructure that India is still developing. The impact is twofold: not only does it inflate production costs, but it also hampers the ability to scale operations independently of foreign suppliers.

Beyond the economic implications, this reliance poses risks to national interests, as over-dependence on a single foreign source can lead to vulnerabilities during geopolitical tensions or trade disputes. Industry reports consistently highlight that China dominates the global supply of EV components, controlling a significant share of raw materials and processed goods essential for production. For Indian manufacturers, breaking this cycle requires substantial investment in alternative sourcing or local production, both of which demand time and capital. Until such capabilities are built, the market remains tethered to external forces, limiting true autonomy in the EV sector.

Underdeveloped Local Supply Chain

Compared to the well-established supply network for internal combustion engine vehicles, India’s EV ecosystem is still in its infancy, lacking the maturity needed to support large-scale production. Suppliers face a daunting challenge: the relatively low sales volumes of EVs do not justify the hefty investments required to set up local manufacturing units. As a result, many hesitate to commit resources, perpetuating a cycle where limited supply chains hinder growth, and slow growth discourages supply chain development. This gap is evident in components like brushless DC motors, which, even when assembled domestically, rely heavily on imported sub-parts to remain cost-competitive.

Adding to the complexity, advanced EV technologies such as high-voltage electronics and power modules are particularly difficult to localize. These require not only cutting-edge technical know-how but also collaboration between original equipment manufacturers and Tier-1 suppliers, a synergy that is yet to fully emerge in India. Industry executives point out that without a critical mass of demand or targeted incentives, building a robust domestic supply base remains a distant goal. The current state of the ecosystem underscores the need for a strategic push to bridge these gaps and create a self-sustaining framework for EV production.

Government Policies and Localization Efforts

PLI Scheme and Localization Criteria

The Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, introduced by the Ministry of Heavy Industries, represents a bold attempt to drive localization in India’s EV sector by offering financial rewards to manufacturers who meet specific domestic value addition (DVA) thresholds. However, the stringent criteria—requiring at least 50% DVA, or 40% if battery cells are excluded—have proven challenging, with only 13% of the 46 EV models sold in India qualifying for benefits. Notably, the six qualifying models belong to domestic giants Tata Motors and Mahindra, while international brands like BMW, Hyundai, and Tesla fall short due to their heavy reliance on imported components, often exceeding 60% of their content.

This disparity reveals a structural imbalance in the market, where homegrown companies with established local networks have an edge over foreign players whose global supply chains are deeply integrated with overseas suppliers. Industry analysts argue that while the PLI scheme’s intent to foster self-reliance is commendable, its strict benchmarks may inadvertently discourage foreign investment in the short term. Adjusting these criteria or providing phased targets could help balance the playing field, ensuring broader participation while still pushing for localization. The current landscape highlights the tension between ambitious policy goals and practical industry constraints.

Ambitious Battery Manufacturing Goals

A cornerstone of India’s strategy to reduce import dependence is the government’s target to establish 50 GWh of battery manufacturing capacity with 60% value addition over the next five years, starting from 2025. This vision aims to position the country as a hub for advanced chemistry cell production, a critical component of EVs. Yet, the road to achieving this is fraught with obstacles, including the high capital costs associated with setting up manufacturing plants and the technical complexities of producing battery cells at scale. Experts caution that progress will likely be gradual, as the industry lacks the immediate resources and expertise needed for rapid advancement.

Furthermore, the financial burden of such initiatives often falls on private players who must navigate uncertain returns in a nascent market. While government support through subsidies and incentives offers some relief, the scale of investment required remains daunting. Industry stakeholders emphasize the need for public-private partnerships to share risks and accelerate development. Without sustained efforts to overcome these hurdles, the goal of domestic battery production risks remaining aspirational, leaving the EV sector vulnerable to external supply constraints for the foreseeable future.

Industry Trends and Future Outlook

Rising EV Adoption and Urgency

As electric vehicles inch closer to capturing a 5% share of car sales in India, the momentum behind EV adoption signals a transformative shift in consumer preferences and environmental priorities. This growing demand, driven by rising fuel costs and increasing awareness of sustainability, presents a golden opportunity for the industry to expand. However, it also amplifies the urgency to build a resilient domestic supply chain capable of supporting this growth. Without a robust local ecosystem, the risk of supply bottlenecks and cost escalations could derail the progress made in market penetration, undermining consumer confidence and policy objectives.

The rapid rise in EV uptake also puts pressure on policymakers and manufacturers to align their strategies with market realities. Stakeholders argue that targeted interventions, such as incentives for local component production and infrastructure development for charging networks, are essential to sustain this momentum. Additionally, fostering consumer trust through quality assurance and competitive pricing will be key to maintaining growth. As the market evolves, addressing supply chain vulnerabilities becomes not just a strategic imperative but a prerequisite for long-term success in the EV space.

Strategic Importance of Self-Reliance

Reducing reliance on foreign imports, particularly from a single dominant source like China, carries profound implications for India’s economic and strategic positioning in the global EV landscape. Achieving self-reliance would not only shield the industry from external shocks like price volatility and geopolitical disruptions but also establish India as a credible player in the international market. This shift could attract foreign investment and partnerships, further boosting the economy while aligning with national goals of sustainability and innovation. The stakes extend beyond mere economics to encompass broader issues of security and autonomy.

Looking back, efforts to address these dependencies have gained traction through policies and industry initiatives aimed at fostering collaboration between automakers, suppliers, and the government. The focus has been on long-term investments in technology and infrastructure to build a self-sufficient ecosystem. Moving forward, actionable steps such as incentivizing research in battery technologies, streamlining regulatory frameworks, and forging global alliances for knowledge transfer could pave the way for success. By prioritizing these measures, India can transform past challenges into a foundation for future leadership in the EV domain.