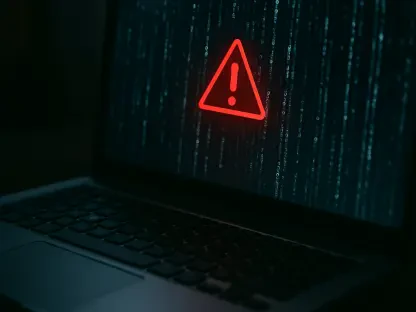

In an era where technology underpins national security and economic strength, the United States faces a critical vulnerability in its reliance on Taiwan for advanced semiconductors, a dependency that has sparked urgent discussions at the highest levels of government and highlighted the need for strategic action. With Taiwan producing a significant share of the world’s cutting-edge chips, particularly through industry giant TSMC, the U.S. finds itself at a crossroads as geopolitical tensions with China escalate. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick recently highlighted the risks of this over-reliance, pointing to China’s explicit intentions toward Taiwan and the danger of concentrating such a vital supply chain on an island so close to potential conflict. This precarious situation has fueled a push for a transformative deal with Taiwan, one that could reshape the global semiconductor landscape. As policymakers and industry leaders navigate these choppy waters, the question looms large: can a strategic partnership with Taiwan bolster U.S. resilience, or will deeper challenges persist in securing a stable future for chip production?

Geopolitical Risks and the Urgency for Action

The semiconductor industry has become a flashpoint in U.S.-China relations, with Taiwan sitting at the heart of this high-stakes arena due to its dominance in advanced chip manufacturing. Commerce Secretary Lutnick emphasized the alarming proximity of Taiwan to mainland China—just 80 miles across the strait—and the explicit threats from Beijing regarding territorial claims. While exact figures on U.S. dependency vary, with estimates suggesting Taiwan supplies around 44% of logic chips and 24% of memory chips to the American market, its role in producing cutting-edge chips below 10nm is unparalleled. This concentration of expertise and production capacity creates a glaring vulnerability, especially as military and economic frictions in the region intensify. A disruption in this supply chain, whether through conflict or political pressure, could cripple critical U.S. industries ranging from defense to consumer electronics, making the need for diversification not just a strategic goal but an urgent national imperative.

Beyond the immediate geopolitical concerns, the broader implications of this dependency touch on economic stability and technological leadership. The U.S. has historically been a pioneer in semiconductor innovation, yet much of its manufacturing has shifted overseas over decades, leaving domestic capabilities lagging. Lutnick’s blunt assessment of the situation underscores a growing consensus across political divides that over-reliance on a single, geopolitically sensitive supplier poses unacceptable risks. The potential for supply chain interruptions isn’t merely theoretical; it’s a looming threat that could undermine everything from smartphone production to advanced military systems. As discussions of a deal with Taiwan gain momentum, the focus remains on mitigating these risks by securing alternative sources and reducing exposure to regional instability. This urgency frames the upcoming negotiations as a pivotal moment in redefining how the U.S. approaches its technological sovereignty in an increasingly uncertain world.

Strategic Moves Toward Domestic Production

A core element of the U.S. strategy to address semiconductor vulnerabilities lies in ambitious plans to boost domestic production, with Lutnick outlining a goal of meeting 40% of national chip needs through local manufacturing in the coming years. This target reflects a broader policy shift under the current administration, which has taken a hardline stance through a reinterpretation of the CHIPS and Science Act. A proposed 1:1 chip rule would require companies to match every imported chip with a domestically produced counterpart or face steep 100% tariffs, marking a departure from earlier incentive-based approaches to more punitive measures. The anticipated deal with Taiwan, described as imminent, could play a crucial role in this framework by potentially expanding TSMC’s commitments in the U.S., including its ongoing projects in Arizona and a reported $100 billion investment over five years for manufacturing, packaging, and research and development.

However, building domestic capacity is not without significant hurdles, as the U.S. must overcome gaps in infrastructure, skilled labor, and technological know-how to compete with established players like Taiwan. TSMC’s Arizona facilities have already begun producing N4 chips, with plans to advance to N3 and N2 nodes by 2028-2029, yet scaling these operations to meet national demand remains a complex endeavor. The Taiwanese government’s reluctance to transfer its most advanced processes abroad under an N-1 policy adds another layer of difficulty, prioritizing the retention of cutting-edge manufacturing on home soil. If the forthcoming agreement can persuade TSMC to bring state-of-the-art node production to American shores, it would mark a historic shift in global semiconductor fabrication. Such a move could significantly enhance U.S. capabilities, reducing dependence on foreign supply chains and fortifying resilience against disruptions in the Taiwan Strait, though the path to achieving this remains fraught with logistical and diplomatic challenges.

Balancing Optimism with Technological Realities

The prospect of a U.S.-Taiwan semiconductor deal carries immense potential to reshape supply chain dynamics, offering a lifeline to American efforts to diversify and localize production amid rising global tensions. The shared understanding across administrations that over-reliance on Taiwan poses strategic risks has driven a unified push for change, even if approaches differ—current policies lean heavily on tariffs and direct leverage compared to previous subsidy-focused strategies. A successful partnership could see TSMC deepen its footprint in the U.S., bringing not just manufacturing but also critical expertise that could catalyze domestic innovation. Yet, optimism must be tempered by the reality that accessing Taiwan’s most advanced technologies remains uncertain, given national policies aimed at safeguarding proprietary processes. This delicate balance between collaboration and competition underscores the complexity of achieving true supply chain security in a globally interconnected industry.

Reflecting on the road ahead, it’s clear that while the groundwork for transformation has been laid through rigorous policy debates and initial investments, the execution of such a deal demands careful navigation of geopolitical constraints and technological barriers. The strides made in highlighting the stakes—through Lutnick’s stark warnings and the administration’s aggressive targets—set a precedent for prioritizing long-term resilience over short-term costs. Moving forward, the focus shifts to actionable steps, such as fostering public-private partnerships to accelerate domestic fab construction and incentivizing workforce development in semiconductor engineering. Additionally, sustained diplomatic engagement with Taiwan emerges as essential to unlock access to cutting-edge capabilities. These efforts, initiated in response to an undeniable crisis, pave the way for a future where the U.S. can stand more firmly on its own technological footing, prepared to weather global uncertainties with greater confidence.