Diving into the critical discussions surrounding the future of global shipping, I’m thrilled to speak with Kwame Zaire, a renowned expert in manufacturing with a deep focus on electronics, equipment, and production management. Kwame’s insights into predictive maintenance, quality, and safety make him uniquely positioned to shed light on the technological and operational shifts needed for a greener shipping industry. Today, we’re exploring the pivotal International Maritime Organization (IMO) meeting in London, where nations are deliberating regulations to drive a sustainable transition in shipping. Our conversation touches on the goals of these new rules, their potential impact on the industry, the push for alternative fuels, and the challenges of balancing environmental goals with economic realities.

Can you walk us through the main purpose of the IMO meeting happening in London this week?

Absolutely, Julien. The IMO meeting is a critical gathering of the world’s major maritime nations to hammer out regulations aimed at steering the shipping industry away from fossil fuels. The core goal is to slash greenhouse gas emissions, which have been climbing as shipping accounts for about 3% of global emissions. It’s a big deal because, if adopted, this could mark the first time a global fee is placed on these emissions, setting a precedent for climate action across industries.

Why do you think this meeting holds such high stakes for the shipping sector?

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Shipping is the backbone of global trade, moving massive cargo volumes over long distances, but it’s heavily reliant on dirty fuels like heavy fuel oil. Without global rules, the transition to cleaner practices becomes chaotic and costlier in the long run. This meeting is about creating a unified framework to push the industry toward net-zero emissions by around 2050, while also protecting public health and marine ecosystems. A failure here means more delays and more pollution.

What are these proposed regulations hoping to accomplish in terms of emissions reduction?

The regulations, often called the Net-zero Framework, aim to progressively lower the greenhouse gas intensity of marine fuels over time. It’s about setting stricter standards for what ships can emit, essentially forcing the industry to adopt cleaner fuels or technologies. The idea is to make high-emission practices unsustainable, both environmentally and financially, by tying emissions directly to costs.

Can you break down how the pricing system for emissions works under this framework?

Sure. The system introduces fees for every ton of greenhouse gas emitted above certain limits. There’s a base compliance level, and a stricter target beyond that. If a ship exceeds the base limit, they pay a hefty fee—think around $380 per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent. If they meet the base but not the stricter target, there’s still a penalty of about $100 per ton. It’s a carrot-and-stick approach, where ships with lower emissions can earn credits to sell, while high emitters have to buy those credits or pay up.

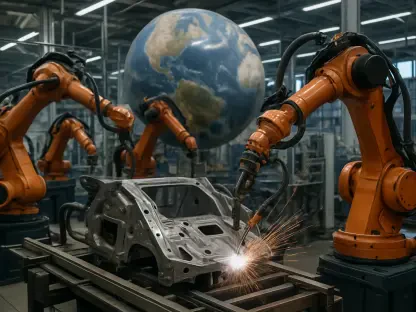

How will shipping companies need to adapt if these rules are put into place?

Companies will need to rethink their entire operations. This means investing in cleaner fuels, upgrading to energy-efficient technologies, or even retrofitting ships for alternative propulsion like wind or electric systems. Large ships, especially those over 5,000 gross tonnage that account for 85% of shipping emissions, will face penalties starting in 2028 if they don’t comply. It’s a massive shift, requiring upfront costs and long-term planning since ships have a lifespan of about 25 years.

What’s the potential financial impact of these fees, and how will the revenue be used?

The fees could generate between $11 billion and $13 billion annually, which is significant. This money would go into an IMO fund dedicated to accelerating the green transition. Think investments in alternative fuel development, rewards for low-emission ships, and support for developing countries to ensure they’re not stuck with outdated, polluting vessels. It’s about leveling the playing field while funding innovation.

What kinds of alternative fuels or technologies are being discussed to help lower emissions in shipping?

There’s a wide range of options on the table. Alternatives to heavy fuel oil include green ammonia and methanol, which are seen as long-term solutions, though they’re not yet cost-competitive. Electricity is another avenue, especially for shorter routes, alongside onboard carbon capture tech. Wind propulsion and energy efficiency upgrades are also gaining traction as ways to cut fuel use. It’s a mix of immediate fixes and future-focused innovations.

What are some of the hurdles in adopting these greener options for ships?

The challenges are substantial. First, the infrastructure for alternative fuels like green ammonia isn’t widely available yet, and scaling it up takes time and money. Then there’s the cost—ship owners are hesitant to invest in unproven or expensive tech without clear incentives. Plus, with ships lasting decades, transitioning an entire fleet isn’t an overnight process. It’s a complex puzzle of economics, logistics, and technology.

There’s been some debate around biofuels in this plan. Can you explain why they’re controversial?

Biofuels are a hot topic because the current rules make them one of the cheapest ways to comply with emission standards. However, many are made from food crops, which can lead to deforestation and push out food production as land gets repurposed. Critics argue this isn’t a sustainable fix and could do more harm than good. There’s a strong push for scalable green alternatives like methanol instead, which don’t compete with food systems.

Looking ahead, what’s your forecast for the future of green shipping if these regulations are adopted or delayed?

If adopted, I see a tough but transformative decade ahead. The financial pressure from fees will drive innovation, though not without growing pains for smaller operators. We could see real progress toward net-zero by mid-century. If delayed, however, emissions will keep climbing, and the industry’s outsized role in the climate crisis will only worsen. The longer we wait, the harder and costlier the transition becomes. I’m hopeful, but the clock is ticking.