The journey of produce from a sun-drenched field to a sterile supermarket aisle is increasingly managed not by the hands of a farmer but by the cold logic of algorithms, transforming pastoral landscapes into highly controlled, data-driven production zones. Modern agriculture stands at a critical juncture, navigating between two profoundly different futures. The dominant trajectory is one of intensifying a century-old industrial model, leveraging digital technology to create hyper-efficient “digital factories” that promise unprecedented yields. This path, however, comes at a steep price, optimizing a system that is a primary architect of climate instability, ecological degradation, and the exploitation of labor. This analysis delves into the evolution and inherent flaws of the digital factory farm and presents a compelling alternative: the “digital garden,” a restorative vision that integrates advanced technology with agroecological wisdom to cultivate a food system that is equitable, sustainable, and fundamentally humane.

The Evolution From Industrial to Digital Control

The concept of agriculture as a manufacturing process is not a recent innovation but has deep roots in the industrialization of the 20th century. Beginning in the 1930s, large agricultural enterprises began a systematic campaign to apply the principles of factory production to the cultivation of land. This industrial logic manifested in the design of harvesting machinery modeled on assembly lines and the implementation of Taylorist management techniques to meticulously track and optimize the output of every farm worker. This paradigm shift fundamentally altered the relationship between humans, nature, and food, reframing the natural world as a collection of raw materials to be controlled and labor as a variable input to be managed for maximum efficiency. This historical precedent established the ideological foundation for the highly mechanized and chemically dependent agricultural systems that dominate the global food supply chain in the current day. This model prized calculability and standardization above all else, setting the stage for a future where technology would amplify this control to an unimaginable degree.

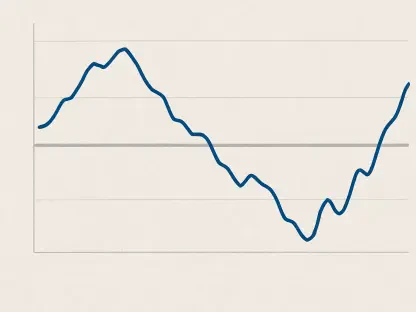

In the 21st century, this industrial framework is undergoing a profound and rapid metamorphosis into what can be termed the “digital factory.” Propelled by the relentless demands of transnational supermarket chains and affluent consumers for year-round access to cosmetically perfect produce, this new iteration of farming draws its inspiration not from the smokestacks of the 20th century but from the data centers of the platform economy. Digital capitalism provides the tools to extend the logic of the factory far beyond the confines of physical walls, enabling a pervasive, real-time system of monitoring and management that envelops both the workforce and the environment. This transformation is not merely an upgrade of existing machinery; it represents a fundamental rewiring of the agricultural process. It seeks to eliminate the final vestiges of unpredictability from farming, creating a system that can respond instantly to market demands and managerial directives, all orchestrated through a complex web of sensors, data analytics, and automated controls.

Pervasive Surveillance in Modern Agriculture

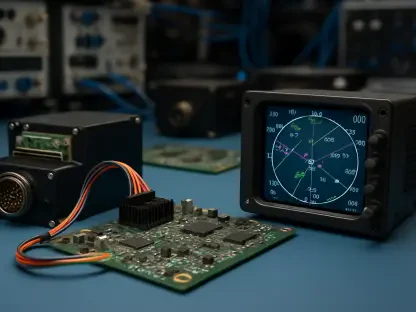

Central to the operation of the digital factory farm is the intense and unblinking surveillance of its human workforce. Agricultural laborers are increasingly subjected to a digital panopticon, a system where their every action is tracked, measured, and quantified. This is achieved through a suite of technologies, including GPS-enabled wristbands that monitor their precise location throughout the workday, QR codes affixed to every harvested box that trace produce back to the specific individual who picked it, and sophisticated machinery that automatically logs harvesting speeds while deducting wages for any unsanctioned breaks. Within the controlled environments of greenhouses and packing facilities, ubiquitous surveillance cameras and output-tracking systems link a worker’s compensation directly to their minute-by-minute productivity. This creates a high-pressure environment of unprecedented digital oversight, eroding worker autonomy and transforming human labor into a data point to be continuously optimized for the benefit of the operation’s bottom line.

This same network of digital surveillance simultaneously serves to intensify the historical effort to subordinate nature to the demands of industrial production. The inherent unpredictability of biological systems—from weather patterns and soil composition to the life cycles of organisms—has always posed a significant challenge to the just-in-time delivery models required by corporate buyers. Digital technology now offers a new frontier in this ongoing struggle for control. For example, data collected from a worker’s GPS tracker does more than just measure their individual performance; it also contributes to a detailed map of the precise yield and quality of produce from each individual tree or plant. This granular data enables what is known as “precision” intervention, allowing farm managers to target specific “underperforming” plants with customized applications of fertilizer or irrigation, or to simply identify them for replacement. This establishes a powerful and continuous feedback loop where the digital surveillance of labor directly facilitates the data-driven manipulation and commodification of the natural world.

Forging a New Path Toward Sustainability

The simple act of digitizing a fundamentally flawed and destructive system cannot be considered a solution; in reality, it serves as an accelerant for its worst tendencies. The digital factory farm, with its reliance on vast, chemical-dependent monocultures, perpetuates an agricultural model that actively pollutes waterways with fertilizer runoff, fosters the emergence of pesticide-resistant “super weeds,” contributes directly to catastrophic biodiversity loss, and exposes farm workers to hazardous conditions such as pesticide poisoning and heat stroke. In an era defined by converging ecological and social crises, the strategy of optimizing a primary driver of these problems is a profoundly misguided endeavor. It represents a path that locks global food systems into an increasingly unsustainable future, all under the guise of technological progress and efficiency, while failing to address the root causes of agricultural instability and injustice.

In the search for viable alternatives, many have turned to the realm of speculative fiction, but the visions presented there often prove to be incomplete or undesirable. One common futuristic trope depicts a world of fully automated, networked machines operating on immense, homogenous fields—essentially a perfected digital factory devoid of human workers, erasing any meaningful connection between people and their food source. At the opposite end of the spectrum, some narratives envision a return to small-scale, agroecological farming performed entirely through arduous and inefficient manual labor, a romanticized vision that ignores the immense physical toil historically associated with agriculture. Both of these imagined futures are ultimately lacking. The true challenge lies in navigating a third way, one that avoids the pitfalls of a future defined by either “farms without people” or “farms without machines” and instead seeks a thoughtful synthesis that integrates technology and ecology in genuine service of human and planetary well-being.

The Digital Garden as a Blueprint for the Future

Remarkably, a compelling blueprint for a more sustainable and equitable agricultural future can be found not in speculative fiction, but in a re-examination of history. During the 19th century, an innovative system of urban farms developed on the outskirts of Paris, managed and operated by working-class citizens. This network of intensive market gardens was astonishingly productive, managing to grow enough fresh produce to feed the entire city of two million people, with a significant surplus available for export. On a per-acre basis, the output of these Parisian farms far exceeded that of the later, petroleum-fueled Green Revolution, providing a powerful historical precedent that demonstrates the viability of localized, hyper-productive, and sustainable agriculture. This model proves that high yields and ecological health are not mutually exclusive goals and that communities can achieve food sovereignty through intelligent design and cooperative effort.

This powerful historical example provided the foundational blueprint for what might be called the “digital garden.” This vision imagines a future where food production has been decentralized, taking the form of a distributed network of cooperative, technologically assisted farms integrated directly into the fabric of communities, potentially on land currently occupied by urban infrastructure like parking lots. In this model, the cultivation of food was no longer the burden of a marginalized and exploited migrant workforce or a small class of landowning farmers but became a shared civic responsibility, with community members contributing a few hours a week to cultivate a local, resilient, and sovereign food supply. This approach not only reconnected people with the source of their nourishment but also fostered a stronger sense of community and collective ownership over the local environment and its resources. The “digital garden” thus represented a fundamental reorientation of the food system, shifting it from a model of extraction and exploitation to one of regeneration and shared prosperity.