The long-prophesied era of the truly smart factory is no longer a distant vision; it has arrived, transforming sprawling industrial complexes from collections of discrete, siloed processes into a single, cohesive, and intelligent organism. This pivotal shift, which gained significant traction in recent months, marks the maturation of the Industry 4.0 framework from concept to tangible reality. At its core is the seamless convergence of pervasive IoT sensors providing the ability to sense, centralized artificial intelligence platforms delivering the ability to decide, and sophisticated, self-adjusting automated equipment offering the ability to act. This integration creates a closed-loop system that operates with a degree of autonomy and intelligence analogous to a factory-sized robot, moving beyond isolated pilot projects to scalable, high-impact deployments that are fundamentally redefining the nature of modern manufacturing.

The Digital Brain and Autonomous Orchestration

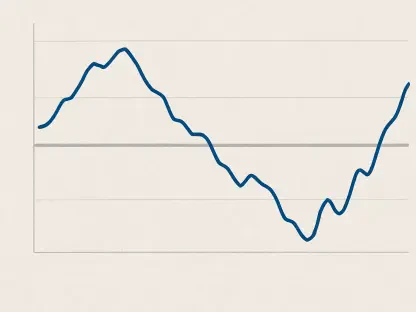

A monumental leap forward in manufacturing efficiency is being achieved by solving historically intractable computational problems, effectively giving the factory a powerful digital brain. A paradigm-shifting pilot project at a BASF facility demonstrated this by utilizing a hybrid quantum-classical computing approach to dramatically compress production scheduling time. What once took a full ten hours to calculate can now be accomplished in a mere five seconds—a staggering 7,200-fold reduction in processing time. This near-instantaneous capability allows scheduling to evolve from a static, pre-determined plan into a dynamic, responsive feedback loop that can adapt to changing conditions in real time. The optimization targeted key performance metrics, yielding a 14% reduction in product lateness, a 9% decrease in equipment setup time, and an up to 18% shortening of tank unloading durations. This trend of tackling complex, system-wide optimization is also seen in supporting infrastructure, with similar hybrid quantum methods being applied to the unit commitment problem for power grids, proving that computational bottlenecks are rapidly becoming a thing of the past.

Building upon this enhanced decision-making power, the concept of industrial AI is evolving from passive “copilots” into proactive “agentic workflows” capable of executing complex, multi-step tasks across industrial software suites with minimal human intervention. Siemens’ Industrial AI agents represent a significant move beyond simple question-and-answer functions toward genuine workflow automation within engineering toolchains. Early deployments at firms like ThyssenKrupp Automation Engineering have already demonstrated practical gains by significantly reducing engineering cycle times. This trend extends beyond the factory floor into scientific research, where national laboratories are employing agentic workflows to autonomously coordinate laboratory instruments, data analysis, and experimental design, creating a much tighter and faster loop between hypothesis and validation. The emergence of this as a distinct market category, estimated to be worth $5.5 billion in 2025, confirms a decisive shift from bespoke, one-off solutions to standardized, deployable tools that empower the autonomous factory.

Virtual Prototyping and Physical Realization

The development and deployment of robotics and physical AI systems have been supercharged by a fundamental change in how their underlying models are trained. The industry is rapidly moving away from the slow, laborious process of collecting real-world demonstration data and is instead “manufacturing” vast quantities of high-quality synthetic data within hyper-realistic simulations. NVIDIA’s Isaac GR00T Blueprint platform exemplifies this approach at an industrial scale, reportedly generating 780,000 synthetic training trajectories in just eleven hours—an output equivalent to 6,500 hours of human demonstration. This capability to generate massive, diverse datasets on demand dramatically compresses development cycles and allows for more robust and capable AI. Amazon’s Blue Jay robotics system, for instance, moved from initial concept to full production in just over a year, a timeline made possible by the rapid iteration and testing that can occur within these rich digital twin environments before any physical hardware is built.

This powerful use of simulation and digital twins now extends far beyond individual robots to encompass the entire facility lifecycle. Industry giants like TSMC and Foxconn are leveraging comprehensive platforms to design, simulate, and optimize every aspect of new fabrication and manufacturing facilities in a virtual world before any physical construction begins. This “virtual commissioning” allows engineers to validate processes, optimize layouts, and identify potential bottlenecks, significantly reducing the risk of costly real-world errors and delays. However, it is crucial to remember that these “AI factories,” both virtual and real, are still bound by the laws of physics. Research from Florida Atlantic University highlights that advanced direct-to-chip liquid cooling can increase GPU cluster throughput by 17% while simultaneously reducing power consumption. This underscores the critical reality that thermal and power management are no longer secondary considerations but have become first-order design principles in this new paradigm of high-density, intelligent manufacturing.

Convergent Fabrication and Advanced Materials

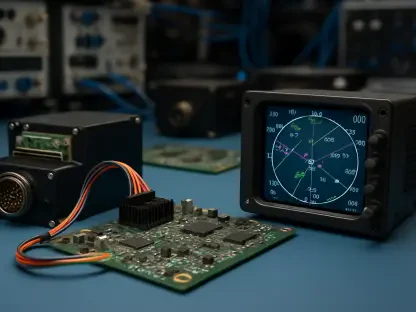

Innovation at the hardware level is increasingly focused on integrating previously separate and distinct manufacturing steps into unified, automated platforms that streamline production from raw material to finished part. A prime example of this trend is Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s “Future Foundries” initiative, which combines wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM), subsequent heat treatment, in-process inspection, and final machining into a single, cohesive, palletized system. This convergence yields significant efficiencies, with the lab reporting an impressive 68% reduction in total production cycle time compared to conventional, multi-stage methods. More importantly, this integrated approach moves quality control upstream, embedding it directly into the fabrication process. By integrating real-time inspection, the platform aims to detect 99% of targeted flaws during the build itself, with a long-term goal of cutting the need for downstream quality control measures by as much as 75%. This is particularly relevant for addressing domestic manufacturing gaps in large, complex metal parts for critical industries.

The aerospace industry continues to serve as a fertile proving ground for the most advanced materials processing techniques, pushing the boundaries of what is physically possible. Recent work by InssTek and the Korea Aerospace Research Institute on the directed energy deposition (DED) of a massive three-ton rocket nozzle showcased this innovation. Their process demonstrated the ability to create functionally graded materials by seamlessly transitioning between different alloys, such as copper and Inconel 625, within a single, monolithic part. This remarkable capability allows engineers to place specific material properties like thermal conductivity and high-temperature strength precisely where they are needed most, optimizing performance without the compromises of traditional assembly. On the commercial front, the progress of companies like Relativity Space with its additively manufactured Terran R rocket, backed by a reported order backlog exceeding $2.9 billion, signals that these advanced, hybrid manufacturing approaches are not just laboratory curiosities but are being validated by significant real-world market demand.

Engineering a Cleaner Industrial Core

A profound and strategic shift is occurring in heavy industry, moving beyond a reliance on post-process carbon capture to fundamentally redesigning core chemical processes to be inherently non-emitting. This approach tackles pollution at its source by engineering decarbonization directly into the plant’s foundational infrastructure, representing a far more permanent and efficient solution to industrial emissions. The ELYSIS joint venture, a collaboration between Alcoa and Rio Tinto, exemplifies this with the 2025 startup of the first commercial-scale inert anode cell for aluminum smelting. This groundbreaking technology completely replaces the traditional carbon anodes used for over a century, releasing pure oxygen as a byproduct instead of carbon dioxide. This single innovation has the potential to eliminate a major source of greenhouse gas emissions from a critical global industry.

This trend toward process reinvention is not isolated to aluminum but is visible across the heavy industry landscape. In the steel sector, SSAB’s HYBRIT initiative continues its determined push toward industrial-scale, fossil-free production, aiming to replace coking coal with green hydrogen as the primary reductant in the blast furnace. This completely alters the chemistry of steelmaking to eliminate its carbon footprint. Similarly, in the cement industry, which is another major source of global emissions, Heidelberg Materials inaugurated the Brevik project in Norway. This landmark facility is the world’s first industrial-scale carbon capture plant fully integrated with a cement production line, demonstrating a viable pathway for an industry long considered difficult to decarbonize. Together, these large-scale projects represent a collective and strategic move away from mitigating pollution to designing it out of existence from the very start.

The Quantified Factory in Practice

The tangible benefits of the quantified, connected factory are becoming increasingly apparent in day-to-day operations like maintenance and quality control, driving real-world improvements in efficiency and reliability. A compelling case study from Siemens on its Senseye Predictive Maintenance platform detailed how a major automotive OEM connected over 10,000 assets across its facilities. Within just twelve weeks of implementation, the company achieved a significant 12% reduction in unplanned downtime by using AI to anticipate equipment failures before they occurred. Reliability is also a direct function of robust connectivity, as demonstrated by Tesla’s deployment of a private 5G network at its Berlin Gigafactory. This ensured seamless and consistent coverage for mobile equipment and automated guided vehicles, a change credited with up to a 90% improvement in “overcycle issues” in one key process.

In the realm of quality control, AI-powered vision systems are enabling comprehensive, high-speed inspection at a scale that was previously impossible. At its Neckarsulm site, automaker Audi now uses sophisticated AI to analyze approximately 1.5 million spot welds across 300 vehicles during every single shift. This achieves a 100% check of these critical connection points, a dramatic leap forward from traditional random sampling methods that could only ever inspect a small fraction of total production. This ability to see and analyze everything moves quality assurance from a reactive, post-production activity to a proactive, integrated part of the manufacturing flow. This relentless drive for precision is mirrored in semiconductor fabrication, where Intel’s 18A node, which reached a critical maturation point, showcases the integration of major architectural shifts like RibbonFET transistors and PowerVia backside power delivery to push the limits of performance and efficiency.

A Transition from Instrumentation to Autonomy

The year 2025 marked the period when the constituent elements of the smart factory transitioned from a collection of isolated technologies into an integrated, autonomous whole for pioneering firms. The narrative shifted decisively from simply instrumenting a factory with sensors to imbuing it with the intelligence to self-optimize and operate as a cohesive, closed-loop system. The evidence for this transformation was compelling and widespread: quantum-level acceleration in production scheduling, the rise of AI-driven automation for complex engineering workflows, simulation-powered robotics development that dramatically shortened innovation cycles, integrated additive manufacturing platforms that merged fabrication and quality control, and the deployment of fundamentally new, cleaner industrial chemistries. The technological capabilities were demonstrably real and delivering significant value. Consequently, the central challenge moving forward was no longer about inventing new technological building blocks, but rather about developing the human infrastructure, integration discipline, and robust governance required to scale these powerful systems. The most significant barrier to widespread adoption became human, not technical, as a substantial skills gap and the challenge of adapting the workforce to this new reality emerged as the primary limiting factors.