We’re joined today by Kwame Zaire, a leading expert in advanced manufacturing and production management, to discuss a groundbreaking development in military logistics. The recent Trident Warrior exercise showcased how deployable metal additive manufacturing, specifically SPEE3D’s cold spray technology, is poised to revolutionize how our forces maintain readiness at the tactical edge. We’ll explore how service members with no prior expertise were rapidly trained to operate this advanced system, the strategic shift from simply replacing parts to repairing them in the field, and the tangible impact this had on operational tempo in a live-fire environment.

The Trident Warrior exercise involved training service members from different branches to operate the XSPEE3D. What was the learning curve like for these non-specialists, and what specific steps did the training involve to get them mission-ready so quickly? Please describe that process.

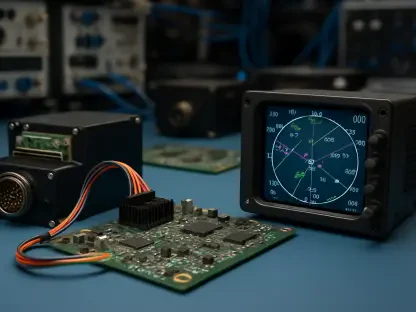

It was remarkable to see just how quickly these service members—soldiers and an airman who weren’t manufacturing specialists—got up to speed. The core question of the exercise wasn’t just ‘does the tech work,’ but ‘can a warfighter actually use it under pressure?’ The training, guided by experts at the Naval Postgraduate School’s facility, was intensely practical. We didn’t try to turn them into materials scientists; instead, we focused on the operational workflow: machine setup, material handling, selecting the correct digital file, and executing the print. The user interface on these systems is becoming more intuitive, which dramatically flattens that learning curve. Within a very short period, they moved from classroom instruction to confidently operating the machine, demonstrating that this technology is mature enough to be adopted by a much broader group of maintainers.

A key success mentioned was the precise repair of a damaged aviation part, not just manufacturing a new one. Could you walk me through the steps of that repair process? What were the main advantages in terms of material savings, labor, and getting the asset back into service?

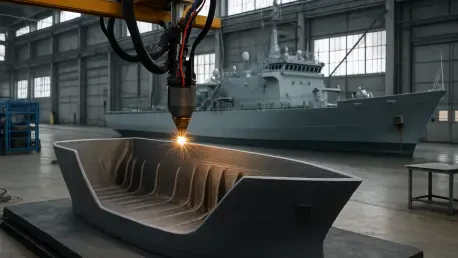

This was, in my opinion, the most significant outcome of the entire trial. Instead of scrapping a complex and valuable aviation component, we demonstrated a surgical repair. The process began with a digital scan of the damaged area to create a precise 3D model of the missing material. That model was then used to program the XSPEE3D to add metal, layer by layer, only where it was needed. You could feel the focus in the air as the machine meticulously rebuilt the component. The advantages are immense. Material waste is almost zero compared to printing a new part from scratch or machining it from a solid block. The labor involved is a fraction of what would be required for a full replacement, and most importantly, the turnaround time is slashed from weeks or months to mere hours, which directly translates to improved readiness.

When a single unavailable part sidelines a platform, logistics become paramount. How did on-demand production during the exercise concretely impact operational tempo? Could you share a specific example or metric demonstrating the time saved compared to waiting on traditional supply chains?

It fundamentally changes the equation for field maintenance. The reality for any maintainer is that a single, seemingly insignificant part can render a multi-million-dollar piece of equipment useless. During Trident Warrior, we moved past the bureaucracy and freight delays of the traditional supply chain. Instead of putting in a request and waiting for a part to be shipped from a depot thousands of miles away, the team could manufacture it right there, at the point of need. While specific time-saved metrics for each part are often classified, the operational impact was clear: downtime was reduced from a matter of weeks to a matter of hours. This means an asset is back in the fight the same day, not next month. That ability to sustain momentum without being hamstrung by a fragile supply line is a strategic advantage.

Testing technology in a live operational environment is very different from a lab. What were the unique challenges of deploying the XSPEE3D in this setting, and how did its performance specifically address the “point-of-need” demands of the Trident Warrior exercise?

Deploying advanced manufacturing equipment into an operational environment is a true test. You’re not in a climate-controlled lab; you’re dealing with the real-world conditions of a naval base, with all the accompanying vibrations, temperature fluctuations, and power inconsistencies. The challenge is ensuring the machine is not just precise, but also rugged and reliable. The XSPEE3D’s cold spray process proved robust enough to handle these conditions and deliver consistent, high-quality results. It directly addressed the “point-of-need” demand because it was fast and deployable. It wasn’t some delicate laboratory instrument. It was a tool that could be set up and used by maintainers to solve problems in real-time, giving commanders more options and ensuring the fleet could maintain its operational readiness without being tethered to a distant industrial base.

What is your forecast for deployable metal additive manufacturing?

My forecast is one of rapid and widespread integration. What we saw at Trident Warrior is the beginning of a logistical revolution. In the next five to ten years, I expect to see these deployable manufacturing systems become a standard part of maintenance and repair toolkits, not just on naval vessels but in forward operating bases and expeditionary airfields across all branches. The technology will become more compact, more automated, and capable of working with a wider range of materials. We are moving away from a model of stockpiling massive inventories of spare parts toward a future of digital inventories, where a part exists as a file until the moment it is needed. This will not only enhance readiness but will also create a more resilient and agile military force.