I’m thrilled to sit down with Kwame Zaire, a renowned manufacturing expert with a deep passion for electronics, equipment, and production management. With his extensive knowledge in predictive maintenance, quality, and safety, Kwame offers unique insights into the groundbreaking achievement by the RAF, where engineers at RAF Coningsby successfully installed the first in-house additively manufactured component on a Typhoon fighter jet. In this conversation, we’ll explore the significance of this milestone, the innovative processes behind it, the challenges faced, and the future potential of 3D printing in military aviation.

Can you explain the importance of the RAF’s recent achievement with the Typhoon fighter jet and why it’s such a game-changer?

Absolutely, Marie. This is a landmark moment for the RAF because they’ve successfully fitted a temporary replacement part for the pylon assembly—that’s the structure connecting weapons systems to the jet’s wing—using in-house additive manufacturing, or 3D printing. It’s a big deal because it demonstrates the ability to bypass traditional supply chain delays. Normally, waiting for spare parts can ground aircraft for weeks or even months, but printing a component on-site slashes that downtime dramatically, keeping jets operational when they’re needed most.

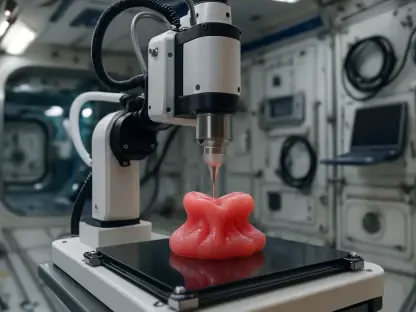

How did the engineers at RAF Coningsby manage to create and install this temporary part?

The process was fascinating. The team started by precision-scanning the damaged component to capture its exact dimensions. This digital data was shared with specialists who then designed a temporary replacement. The actual manufacturing happened at the Hilda B Hewitt Centre for Innovation, which is equipped with cutting-edge 3D printing and scanning tech. From there, the part was crafted and handed over for installation. It’s a streamlined workflow that shows how advanced tools and skilled engineers can come together to solve real-time problems.

What can you tell us about the key teams behind this project and their specific contributions?

Two squadrons played pivotal roles here. No 71 Inspection & Repair Squadron was instrumental in designing and manufacturing the temporary part. They’re experts in repairing aircraft structures and creating innovative fixes when standard solutions aren’t available. Then, the engineers from 29 Squadron took over to install the component on the Typhoon. Their hands-on expertise ensured the part was fitted correctly and ready for operational use. It was a seamless collaboration between design and execution.

This temporary part isn’t meant to be a long-term solution. Can you shed light on why that is?

That’s right. This 3D-printed part is an interim fix, not a permanent one. Temporary components like this are often made from materials or with processes that meet immediate needs but may not match the durability or exact specifications of the original manufacturer’s part. It’s designed to keep the jet flying while a permanent replacement—likely made with stricter standards and testing—is developed. Typically, a temporary fix might be used for a short period, just enough to bridge the gap until the final part arrives.

Why is reducing aircraft downtime so critical for the RAF, and how does in-house printing help?

Downtime is a major headache for any air force. When a jet is grounded waiting for parts, it’s not just sitting idle—it’s unavailable for missions, training, or defense readiness. That can compromise operational capability, especially in urgent situations. In-house printing tackles this by cutting wait times. Instead of relying on external suppliers, which can take weeks, engineers can produce a usable part in days or even hours. It’s about maintaining readiness and ensuring the fleet is always mission-capable.

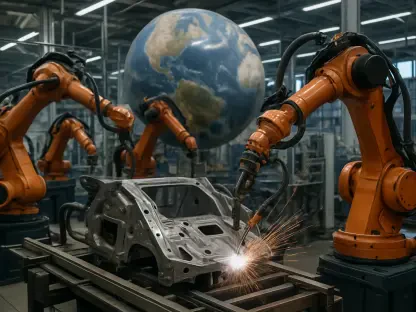

There’s talk of this technology having broader applications. What’s the potential for 3D printing in the RAF’s future?

The potential is enormous. This success with the Typhoon could pave the way for printing other components across different aircraft in the RAF fleet. Imagine a future where bases are equipped with advanced manufacturing hubs, producing parts on-demand for everything from fighters to transport planes. It could revolutionize maintenance by reducing costs, minimizing reliance on complex supply chains, and boosting aircraft availability. We’re looking at a shift toward more self-sufficient, agile operations.

What kind of challenges did the team likely encounter while working on this project?

I’m sure there were hurdles. Scanning a damaged component accurately can be tricky—any small error in the digital model could lead to a part that doesn’t fit or function properly. Then there’s the challenge of material selection; the printed part has to withstand the stresses of flight, even if temporarily. Ensuring safety and reliability would’ve been paramount, likely involving rigorous testing and validation to confirm the part could handle operational demands without risking the aircraft or crew.

How does in-house manufacturing like this impact costs and efficiency for the RAF?

It’s a significant win on both fronts. Producing parts in-house is often far cheaper than sourcing them from original manufacturers, especially when you factor in shipping and expedited orders. More importantly, it boosts efficiency by keeping aircraft in service rather than grounded. For critical missions, having a jet ready to fly can be priceless. This approach minimizes financial waste and maximizes operational uptime, which is a huge advantage in military contexts.

Looking ahead, what is your forecast for the role of additive manufacturing in military aviation?

I’m incredibly optimistic. Additive manufacturing is poised to become a cornerstone of military aviation maintenance. In the next decade, I expect we’ll see more bases adopting this technology, with expanded libraries of printable parts and even mobile 3D printing units for deployed forces. It’ll likely integrate with AI and predictive maintenance to anticipate part failures before they happen, printing replacements proactively. The endgame is a more resilient, cost-effective, and responsive military fleet, ready to adapt to any challenge.